26 January 2026

Report I: Governance and the Domestic Balance of Power after Two Years of War on the Gaza Strip

Gaza War reshaped Palestinian society: priorities shifted from growth to basic services; trust mixed but satisfaction fell; civil liberties eroded. Public still values democracy yet increasingly favors a strong leader who can deliver stability. Politically, Fatah's support has collapsed, while Hamas has maintained its base, but the largest group is the politically alienated. Social norms grew more conservative. This landscape signals a deep crisis of governance and a public desire for new leadership.

8-26 October 2025

These are summary findings from the latest round of the Arab Barometer survey in Palestine, the ninth since these surveys began in the Arab world nearly twenty years ago. The survey was conducted by the institute for Polling and Survey Research West Bank and Gaza Strip during 8–26 October 2025.

The period preceding the survey witnessed several important developments, including the continuation of the war on the Gaza Strip until a ceasefire was reached two days after fieldwork began. In the West Bank, settler violence and terror continued against vulnerable, unprotected Palestinian towns without intervention by either the Palestinian or Israeli police to stop these assaults—indeed with complicity and even encouragement in some cases from the Israeli government and with the army providing protection to settlers only. The Israeli army enforced closures on Palestinian areas and restricted Palestinians’ access to main roads in the West Bank.

The ceasefire in the Gaza Strip came as part of what is known as the 20‑point Trump Plan, which made no reference to the situation in the West Bank. The period before fieldwork also saw a sharp decline in government services due to Israeli punitive measures against the Palestinian Authority (PA), including the seizure of clearance revenues, which forced the PA to pay only a portion of public‑sector salaries and curtailed its ability to provide many basic services. Israel also imposed stringent conditions, demanding “reforms” rejected by Palestinian public opinion—such as amending school curricula and halting payments to the families of prisoners and martyrs.

This first report on the results of the ninth Arab Barometer (AB9) survey in Palestine addresses two important issues: governance and the internal balance of power in the Palestinian territories. Subsequent reports will cover other aspects of the findings, such as conditions in the Gaza Strip, peace, and international relations. Although the focus here is on AB9 findings regarding these two topics, the report compares them to those of the previous AB survey conducted two years earlier.

It should be noted that most governance‑related topics in this report were not asked in the Gaza Strip due to the war conditions; in Gaza the focus was on living and humanitarian conditions and other topics related to the Gaza war.

Methodology: |

Interviews for AB9 were conducted face‑to‑face between 8 and 26 October 2025 with a random sample of 1,655 adults across 160 residential localities in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and Jerusalem. The sample size was 855 in the Gaza Strip and 800 in the West Bank, in 80 locations in each; the margin of error was ±3%. All West Bank interviews were conducted in “counting areas,” as defined by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. In the Gaza Strip, interviews were held in 33 counting areas; the remainder were conducted in a representative sample of shelters, built-up and tent shelters, selected by systematic random selection, with quotas to represent areas destroyed by the war or those that were not safely accessible because they were under Israeli military occupation. For comparison, this report cites another survey conducted in late September/early October 2023—i.e., just before October 7 of that year—the eighth Arab Barometer (AB8) survey. The Palestine reports for that survey can be found here: |

Main Findings: A Society in Transition: Palestinian Public Opinion Before and After October 7 |

This first report of AB9 in Palestine examines governance under the PA, as well as the internal balance of power. A comparative analysis of the two Barometer surveys conducted in Palestine—on the eve of the October 7, 2023 attack (AB8) and two years later in October 2025 (AB9)—reveals a society profoundly reshaped by war, trauma, and political disappointment. The results portray a public whose immediate priorities shifted from the economy to survival; whose trust in institutions changed selectively; and whose views on governance, democracy, and leadership hardened in response to a harsh new reality. Comparing AB8 and AB9 provides a data‑driven narrative of a Palestinian society transformed by the shock of war. The period between the eve of October 7, 2023 and October 2025 was a rupture: it accelerated some pre‑existing trends and generated entirely new social and political dynamics. The data point to four key insights into this new reality.

First, the war reshaped public priorities: The Gaza war changed Palestinian public priorities, not only in the Gaza Strip—as a later report will show—but also in the West Bank. Before the war, Palestinians, like many publics, prioritized long‑term economic development. AB8 data showed the economy as the dominant concern. AB9 reveals a notable shift: as life itself came under threat, the public re‑prioritized basic needs—education and health. In the West Bank, demand for education and health care rose while concern with economic development receded: the percentage of those prioritizing education increased from 25% to 30%. This is not merely a change of opinion; it reflects a society grappling with existential fears—an indicator of a population in survival mode, where the building blocks of a functioning future take precedence over abstract economic growth. This foundational shift explains why, despite a rise in trust in some institutions, satisfaction with government performance collapsed precisely in these sectors. Public demand for basic services has become existential, and the PA is failing to meet it. While trust in some government institutions rose slightly, satisfaction with government performance actually fell—particularly in the vital education and health sectors. The public remains highly pessimistic about the PA’s ability to address core challenges like unemployment, price inflation, and security. Meanwhile, the desire to emigrate is growing, driven by a potent mix of economic despair, security fears, and political hopelessness.

Second, the public sits in a deep governance paradox: it yearns for democracy yet is increasingly willing to accept authoritarianism in exchange for stability. Politically, the Gaza war sparked a large increase in public interest in politics—from 29% to 39%—as Palestinians confront existential questions about their future. Yet this heightened interest is accompanied by a bleak assessment of civil liberties: beliefs that freedom of expression and the right to protest are guaranteed collapsed, with only 16% and 13% respectively feeling these rights are protected. This has fueled a desire for faster, more decisive reform, even as a cautious majority still prefers gradualism. Despite these pressures, baseline attitudes toward democracy remain surprisingly stable: both waves show strong, steady, and principled support for democracy as the best system of governance—60% still hold this view. However, the war exposed a deep pragmatism born of despair. While Palestinians value democracy in principle, an increasing majority now prioritizes a strong leader (51%, up from 41%) who can deliver economic stability and impose order, even at democracy’s expense. This shift is reflected in the public’s deteriorating view of Western democracies, with a sharp drop in confidence in the American and German models. Although the principled preference remains, lived experience since October 7—of chaos, violence, and institutional collapse—has severely eroded confidence in democratic practice. The sharp rise in support for a “strong leader” and the prevalent belief that order and economic stability outweigh the type of political system are the clearest indicators. Palestinians have not abandoned democratic rights—as evidenced by anger over declining civil liberties—but they have lost faith in any democratic process’s capacity to rescue them from the current crisis. This has opened a dangerous window for a form of “authoritarian pragmatism.”

Third, the internal political map has been redrawn—but not in the way many outside observers might expect: the immediate outcome is not increased support for Hamas, but rather a catastrophic collapse of Fatah and PA legitimacy in the West Bank. Fatah’s voter base has nearly halved, an indictment of its inaction and loss of initiative during the war. Fatah’s support in the West Bank has collapsed—from 23% to 14%—while Hamas’s support remained relatively stable and even dipped slightly in Gaza, where it maintained its core base, leaving it a permanent actor that cannot be ignored in any future political arrangement. The real “winner,” however, is deep, broad political alienation: over half of the population refuses to align with or identify with any faction. In a hypothetical presidential election, imprisoned Fatah figure Marwan Barghouti remains the frontrunner, clearly outpacing both Hamas’s Khaled Mishal and the incumbent President Mahmoud Abbas. Barghouti’s sustained popularity is crucial: he is not merely a Fatah leader; he symbolizes a different politics—combining resistance with a vision of unity and clean governance. His continued lead in presidential polling across both waves confirms that the public seeks a leader who can transcend the failed models of both the PA and Hamas.

Fourth, the war appears to have triggered a social retrenchment toward more conservative, traditional norms, especially regarding gender roles: Along with religiosity remaining high, there is a notable increase in support for traditional gender roles: 75% now agree that men are better suited as political leaders—up sharply from 63% two years ago. This suggests societal retrenchment in response to instability and deep crisis. The sharp rise in the belief that men are better political leaders is a significant, troubling development. In times of acute crisis and social collapse, societies often revert to traditional hierarchies and patriarchal structures as imagined sources of order and stability. This finding indicates that the shock of war has not only reshaped Palestinian politics but has also begun to undo some social progress achieved in previous years, with long‑term implications for women’s rights and participation in public life.

In short, Palestine in late 2025 is a society scarred by loss, defined by disappointment, grappling with fundamental questions about its future. The public is more politically engaged but feels less free; desires democracy but longs for stability; and is deeply alienated from its current political leadership. These Arab Barometer findings do not point to an imminent solution or a clear path forward, but they paint a vivid portrait of a people at a historic crossroads, forced to navigate a landscape in which many old certainties have been swept away.

1) Media |

The war reshaped media consumption habits. While social media remains a primary news source for 60% of Palestinians, its dominance has fallen from 74% in 2023. Television, by contrast, has made a dramatic comeback, with 35% now relying on it as a main news source, up from just 17%—likely due to the war in Gaza and daily TV coverage. Al Jazeera remains overwhelmingly the dominant and most trusted news outlet, cited by 85% of respondents as their top source of news.

2) Public Priorities, Trust in Institutions, and Satisfaction with Government and Service Delivery: |

Priorities: The Gaza war altered some public priorities in the West Bank. Before the conflict, economic concerns were paramount: in AB8, 25% of West Bankers cited economic development as their top priority. By AB9, economic development is no longer the top priority, standing today at 23%, as it is overtaken by a rise in the prioritization of education (up from 25% to 30%) and health (from 13% to 15%). This shift reflects a society grappling with disruption and anxiety, in which the core pillars of social well‑being take precedence over long‑term economic growth.

Trust in government: Paradoxically, even as daily life became more dangerous, trust in some public institutions—including the government—saw increases, albeit modest in some cases. This may reflect a “rally around the flag” effect during a national crisis. Seventy‑one percent say they distrust or trust the Palestinian government only a little, while just 25% say they have trust or great trust—an eight‑point increase from 17% two years earlier (AB8).

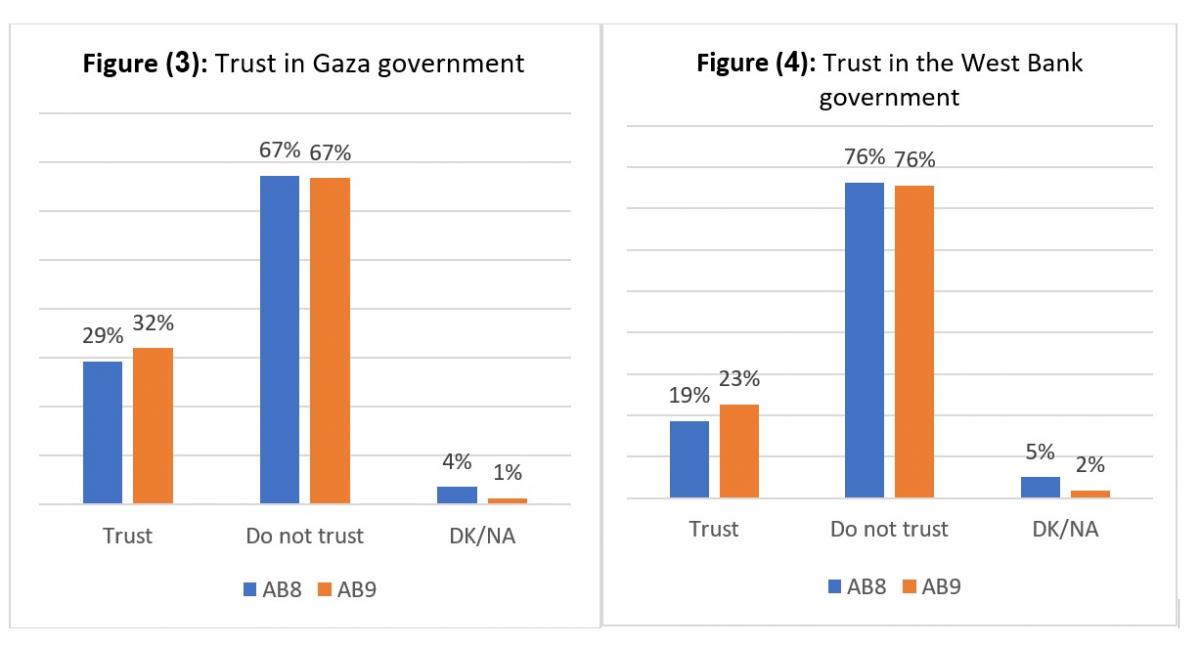

When West Bank residents were asked about trust in the PA government in the West Bank, 23% said they trust it and 76% said they do not (vs. 19% and 76% respectively two years earlier). When Gaza Strip residents in AB9 were asked about trust in the Gaza government (i.e., Hamas’s government), 32% said they trust it and 67% said they do not.

Trust in the PA president: In the West Bank, distrust of the PA president rose by five points to 77%, while trust fell from 22% in AB8 to 19% in AB9.

Trust in the police and National Security Forces: In the West Bank, trust in the Palestinian police rose to 47% (from 38% two years ago), while distrust stands at 53% (down from 58%). Notably, distrust of the National Security Forces is higher than distrust of the police—an unusual change from two years ago, when distrust levels were identical. The likely reason is the heightened sense of threat from Israeli settlers and the public perception that the National Security Forces are not protecting them from this threat, despite the forces’ raison d’être and the significant resources allocated to them—compared to the police, which are responsible for crime prevention. Nonetheless, perhaps due to growing fear of external threats, trust in the National Security Forces in the West Bank is 39% (up five points), and distrust is 58% (unchanged from AB8). Two years ago, trust stood at 34%.

Perception of safety: AB9 shows a clear rise in feelings of insecurity. In AB8, when West Bankers were asked about safety in their area or neighborhood, 74% said their area was very or somewhat safe, while only 26% said it was unsafe. AB9 found that the sense of safety has dropped to 58%, while the sense of insecurity has risen to 42%.

Trust in the courts and judiciary: Sixty‑three percent of Palestinians express distrust in the courts and judiciary, while 34% express trust. Two years earlier, just 27% said they trusted the courts and legal system.

Trust in civil society: Trust in civil society organizations rose to 38% in AB9, up from 27% in AB8 (2023). Fifty‑nine percent say they do not trust CSOs.

Trust in religious leaders: Trust in religious leaders stands at 25%, a six‑point increase over AB8 (2023). In AB9, 71% express distrust in religious leaders.

Trust in Hamas: AB9 indicates a huge increase in trust in Hamas—from 18% in AB8 to 46% in AB9. Forty‑three percent say they do not trust Hamas.

Trust in aid and service institutions in Gaza: We asked Gaza residents about their trust in three institutions: UNRWA, the Red Crescent, and the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation. Trust in UNRWA stands at 75%; in the Red Cross at 66%; and in the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation at 22%.

Satisfaction with government performance: We asked the Palestinian public in the West Bank about satisfaction with overall government performance and with specific sectors such as the education system, health care, garbage collection, electricity provision, and water supply. Despite nominal increases in trust in public institutions, AB9 found a decline in overall satisfaction. Satisfaction with government performance fell slightly from 32% to 29%, with a catastrophic collapse in satisfaction with the education system (from 44% to 21%). The public remains highly pessimistic about the PA’s ability to address core challenges such as unemployment (13% satisfied), narrowing the gap between rich and poor (14%), or reducing prices (11%).

• Overall satisfaction with government performance is 29%, and dissatisfaction 69%—a three‑point decline in satisfaction compared to AB8.

• Satisfaction with the education system is 21%, dissatisfaction 78%—a 23‑point drop in satisfaction compared to AB8 (2023).

• Satisfaction with the health care system is 47%, dissatisfaction 53%—a six‑point decline in satisfaction from AB8.

• Satisfaction with garbage collection is 70%, dissatisfaction 30%—an 18‑point increase in satisfaction compared to AB8.

• Satisfaction with electricity provision is 76% (dissatisfaction 24%); satisfaction with water availability is 47% (dissatisfaction 52%).

Assessment of government performance: We asked West Bank Palestinians to assess government performance in three areas: providing security, narrowing the rich‑poor gap, and keeping prices low:

• Positive assessment (“good” or “very good”) for providing security is 31%; negative assessment (“bad” or “very bad”) is 67%—a two‑point drop in positive assessment compared to AB8 (2023).

• Positive assessment for narrowing the gap between rich and poor is 14%; negative 80%—a two‑point increase in positive assessment from AB8 (2023).

• Positive assessment for “keeping prices low” is 11%; negative 89%—a four‑point rise in positive assessment compared to AB7.

Government responsiveness: We asked West Bank residents how responsive the government is to people’s demands. Only 17% believe the government is very or largely responsive; 81% say it is not very or not at all responsive. These views are similar to AB8 when 16% said the government was responsive and 83% said it was not.

3) Perceptions of Corruption and Government Anti Corruption Efforts |

An overwhelming majority of West Bank Palestinians (87%) believe there is corruption in PA institutions—either to a great extent (62%) or to some extent (24%). Five percent say it exists to a small extent, and 4% say it does not exist at all. These results are lower than in AB8, when 94% of West Bank Palestinians believed there was corruption in PA institutions—either to a great extent (67%) or to some extent (27%)—and slightly lower than AB7 (2021).

We also asked about the extent of government efforts to combat corruption. Sixty‑nine percent believe the government is not fighting corruption at all or is doing so only to a small extent (44% “not at all,” 25% “to a small extent”). By contrast, 29% believe it is fighting corruption (5% “to a great extent,” 24% “to a moderate extent”). In 2023, 64% believed the government was not fighting corruption or only to a small extent, and 35% believed it was (12% “great extent,” 23% “moderate”)—a six‑point decline in the percentage of those who think the PA is combating corruption.

4) Political Participation, Freedoms, Democracy, Migration, and Social Attitudes |

The war on the Gaza Strip led to a notable increase in public interest in politics—from 28% to 39%. Yet this increased interest is accompanied by a bleak assessment of civil liberties under the PA: the share believing freedom of expression is guaranteed fell from 27% to 16%, and the share believing the right to participate in demonstrations is guaranteed fell from 25% to 13%. This has fueled a desire for faster, more decisive reform, with the share preferring immediate, one‑off reforms rather than gradual reforms rising from 32% to 38%.

This has likely contributed to a growing sense of despair. Despair is evident in the desire to emigrate: a quarter of West Bank residents (24%) now consider leaving Palestine, driven primarily by economic reasons (71%), security (38%), and politics (37%)—all notably more prominent since 2023 when only 21% expressed a desire to emigrate.

Despite these pressures, baseline attitudes toward democracy remain surprisingly stable: 60% still see it as the best system of governance. However, the war has revealed a deep‑seated pragmatism born of despair. While Palestinians value democracy in principle, a slim majority now supports a strong leader (51%, up from 41%) who can deliver stability and order, even at the expense of democratic practice. This is reinforced by the belief of 68% that the nature of the political system does not matter so long as the government is able to solve economic problems. The war has also worsened views of Western democracies, with positive evaluations of American democracy falling from 57% to 42% and of German democracy from 56% to 42%.

The war has also left its mark on socio‑religious attitudes. While overall religiosity remains high and largely stable, there is a marked shift toward more conservative gender norms. The percentage of those who agree that men are better suited as political leaders rose from 63% to 75%. Similarly, the share who believe men should have the final say in family matters rose from 44% to 57%. This signals a societal shift toward traditional patriarchal structures in response to instability and deep crisis.

5) Leadership and the Domestic Balance of Power |

We examined the domestic balance of power among Palestinian political parties in three ways: support for different political leaders, party support, and parliamentary voting behavior.

Presidential elections: To gauge the popularity of Palestinian figures, we asked about voting intentions in a hypothetical race among the incumbent President Mahmoud Abbas and the two most popular and well‑known rivals: Fatah’s Marwan Barghouti and Hamas’s Khaled Mishal. The question on leaders’ popularity was restricted to the Gaza Strip and was not asked in the West Bank, which typically tends to support Marwan Barghouti and reject President Abbas. In a hypothetical presidential election, Fatah leader Marwan Barghouti remains the frontrunner in the Gaza Strip, with 30% of the vote, followed by Hamas’s Khaled Mishal (22%), while the incumbent Mahmoud Abbas trails far behind at 13%. These figures do not differ significantly from 2023, indicating that Barghouti’s standing as a symbol of resistance and unity transcends the immediate political aftershocks of the war—even though he, like Abbas, is a Fatah leader at a time when Fatah’s popularity has collapsed, as discussed below. Thirty‑four percent say they would not participate in such an election. In AB8, the results were 32% for Barghouti, 24% for Hamas’s then‑candidate Ismail Haniyeh, and 12% for Abbas.

Factional support: The party support question was restricted to the West Bank and not asked in Gaza. When asked “Which party is closest to you?”, respondents chose Fatah at 18% (vs. 30% before the war in AB8), Hamas at 24% (vs. 17% before the war), third powers at 7% (vs. 6% before), while a slim majority of 51% (vs. 47% before) chose “none of the above.”

|

Parliamentary elections: AB9 examined voting behavior in both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip—how respondents would vote in new legislative elections in each area. The results show that the Fatah vote share is 16% (14% in the West Bank, 19% in the Gaza Strip), compared to 24% in AB8 two years earlier; the “Change and Reform” list (Hamas) stands at just 19% (17% in the West Bank, 22% in Gaza). Ten percent would vote for third parties that competed in the last legislative elections in 2006, and 14% would vote for none of the competing parties.

The reason the Fatah and Hamas vote shares are lower than the simple party support figures cited above is that a large number of respondents refuse to participate in elections. Non‑participation in this survey stands at 41% (47% in the West Bank and 32% in Gaza). In other words, the survey found that 55% of the overall public either refused to vote or chose “none of the above.” When voting is limited to those who would actually participate, Fatah’s share rises to 27% (25% in the West Bank, 28% in Gaza), Hamas’s to 33% (33% in the West Bank, 32% in Gaza), and the undecided—or those who chose “none of the above”—to 24%.

Notably, among likely voters, Hamas’s vote share in AB9 is higher among those aged 30 and above (35%) compared to just 25% among 18–29‑year‑olds. By contrast, the undecided share among youth reaches 27%, while among older voters the third party and undecided shares are 15% and 23% respectively. Religiosity is a better indicator of intended voting patterns: Hamas support is 34% among the religious, 32% among the moderately religious, and 9% among the non‑religious. Fatah’s support is 25% among the religious, 28% among the moderately religious, and 43% among the non‑religious. Third party support is 21% among the religious, 12% among the moderately religious, and 18% among the non‑religious. The undecided are drawn primarily from the non‑religious and moderately religious, and lastly from the religious.

AB9: Demographic variables affecting electoral behavior.

Electoral lists | Men | Women | 18-29 | 30 years and above | Religious | Somewhat religious | Unreligious |

Fatah | 30% | 23% | 26% | 27% | 25% | 28% | 43% |

Change and Reform (Hamas) | 30% | 36% | 25% | 35% | 34% | 32% | 9% |

Third parties | 15% | 19% | 22% | 15% | 21% | 12% | 18% |

Undecided | 26% | 22% | 27% | 23% | 20% | 28% | 30% |